Chinese New Year: Celebrating the Music of China

Posted on 13th January 2016 at 14:00

Chinese New Year falls on the 8th of February in 2016. It is a public holiday marking the first day of the lunar calendar, so the date is different each year. The occasion centres around New Year’s Eve, the day of family reunions, and New Year’s Day, a day of close family visits and new year greetings, but celebrations often begin three weeks before. As we head into the Year of the Monkey, the Music Workshop Company takes a look at ancient Chinese music and the fantastic stories that accompany it.

The music of China has an extraordinary history stretching back thousands of years. Documents and artefacts give evidence of an advanced musical culture as early as 1125 BCE, when the emperors of the Zhou dynasty were in power.

According to Chinese mythology, music was created by Ling Lun, a scholar who lived around 2700 years BCE. Lun was sent by Emperor Huangdi, the Yellow Emperor, to the western mountain area to cut bamboo pipes that could emit sounds matching the call of the immortal bird, the phoenix or fenghuang.

The formal system of court and ceremonial music in China was established during the Zhou dynasty, almost 3,000 years ago. At this time, music was conceived as a manifestation of the sounds of nature, with its yin and yang, complimentary and opposing forces. A system of pitch developed based on a ratio which symbolised heaven and earth, and on a pentatonic scale which derived from a circle of fifths theory.

Chinese philosophers took various views. To Confucius, music was vital for the refinement and cultivation of the individual, whereas the philosopher Mozi argued that music was an extravagant indulgence, and potentially harmful. In ancient times, in order to be considered a scholar, the study of music was integral, alongside that of calligraphy, painting and board game.

Instruments in ancient Chinese music were classified under eight categories, depending on the materials that made the sound.

Jin – metal

Shi – stone

Si – silk

Pao – gourd

Zhu – bamboo

Tu – clay

Ge – hide

Mu – wood

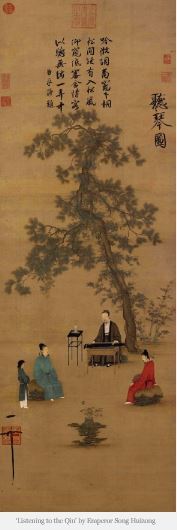

At this time, instrument called the qin was significant. The qin is sometimes called The Instrument of the Sages, and is associated with Confucius. It is now called the guqin, literally meaning ancient instrument. The word qin means both instrument and music. In fact, the word qin is still integrated into many Chinese names for instruments. The Chinese word for piano is Gāngqín.

The guqin is a seven-string instrument of the zither family. An ancient example of the qin was among instruments excavated from the tomb of the Marquis Yi of Zeng, which was made around 433 BCE. Originally a five-stringed instrument, a sixth string was added to the qin around 1000 BCE by the Emperor Wen of Zhou, in mourning for his dead son. Emperor We of Zhou then added a seventh string to increase morale.

The body of the qin is made of wood, but the strings were made of silk, hence it was categorised as si, because it was the silk that made its sound. Interestingly, the ancient Chinese symbol for music was a combination of wood and silk, and the word music also means joy.

The sound of the qin is quite aesthetically unusual. Techniques include sliding up and down the string, even when the sound has already become inaudible. The string is plucked, but its resonance is used for several notes. Instead of trying to force a sound out of the string the player allows the natural sounds to emit from the strings. This sliding on the string even when the sound has disappeared creates a space or void in a piece. A deep connection is created with the listener, as whilst the player continues to slide, the listener fills in the notes in his mind.

There are many other traditional instruments which make up the unique sound of Chinese music. The erhu is a two-stringed bowed instrument that far predates the modern violin, originating about a thousand years ago.

Many Chinese instruments underwent changes in the early to mid 20th century. Most are now tuned with western tempered pitch and this has very much altered the sound of Chinese music. To increase volume, string instruments are often strung with steel or nylon, rather than silk.

In this performance on guqin, traditional silk strings are used. The music, from the Song dynasty, accompanies a poem written by Jiāng Kuí, a famous Chinese poet, composer and calligrapher who lived between approximately 1155 and 1221. This translation is given with the video:

"When winds breathed slowly

and carried cotton blossom drifts

floating from the willow strands,

there in the fragrant willowshade,

we rested in green depths.

Sailing round faraway beaches,

sailing as evening falls;

in this total disorder

of aimless sailing,

where can I make land?

I’ve met my share of mankind,

but none are like the willows by that

gate of departure. None remain.

If trees had hearts like men do,

they would not be so green with life.

Night comes on, your high city disappears,

There’s only the tangle of endless mountains.

Like Wei Lang, I’ve left you-

But remember; this bracelet of jade;

believe this promise that we’ve made

When I left, you begged me “Soon return!”

For fear we’d leave the red flowers loveless.

And I didn’t take your pair of scissors with me,

but if I had, I still couldn’t cut

these thousand binding, silken threads

of melancholy exile."

Share this post: