Claudio Monteverdi: 450 Years of Inspiration

Posted on 15th May 2017 at 15:45

May 15th 2017 marks the 450th anniversary of the birth of Claudio Monteverdi.

Born in 1567, in Cremona, Italy, Monteverdi was famous during his lifetime as a musician and composer, and his works are still regularly performed today.

Cremona is a city with a vast musical heritage. It was home to lute makers, later becoming renowned as a centre for musical instrument making, and home to the Amati, Guarneri and Stradivari violin making families. The historic feudal system – the myriad noble families ruling Italy at the time – laid the way for music to develop, supported and funded by the court, offering employment and opportunity for musicians.

Monteverdi thrived in this musical hotbed, exploring and developing music far beyond his contemporaries. He is nowadays considered to provide a transition between the Renaissance and Baroque periods – and his compositions influenced 20th century composers such as Stravinsky.

One of the main differences between Renaissance and Baroque music is the move from counterpoint to melody with accompaniment. Much Renaissance music was based on imitation and variations, with ground bass or ostinato, where a tonal structure and multi-movement forms emerged in Baroque music – functional harmony based on a central tonic with a strong harmonic flow and tonal sequences such as the circle of fifths.

Many of these ideas were introduced and popularised in the work of Monteverdi.

Monteverdi began his musical studies at the Cathedral in Cremona, producing his first published works – a collection of sacred songs – at the age of 15. After his studies were complete, he was employed as a court musician for the Duke of Mantua, where he initially worked as a singer and viol player before a promotion to music director.

It can be difficult to see historic figures in a human light, but Monteverdi’s life was full of drama; a nice parallel with the plays of Shakespeare, which were written and premiered during his lifetime over in England.

He tragically lost his wife and his baby daughter, he was robbed at gunpoint by a highwayman, on the death of his employer, the Duke of Mantua, he was fired by the Duke’s successor who could not afford to keep him on, leaving the composer with virtually no money, and he was ambitious, planning to show his music to the Pope. By his mid-40s, he was the most celebrated composer in Italy.

His work L’Orfeo is the earliest surviving opera still regularly performed today.

The beginning of opera as a genre is unclear. The concept was born partly by Florentine intellectuals who were fascinated by the dramas of ancient Greece. But the idea was probably gestating long before 1600. Admiration for antiquity was a strong trend in Renaissance Italy, but the recreation of Greek tragedies was not the sole intent of opera composers.

There was a strong interest in the bucolic, pastoral story – nymphs and gods were featured rather than kings and queens. Instrumental music was increasingly integrated into dramatic performances and madrigals were used as interludes in more serious theatrical court productions. Legends such as that of Orpheus were incredibly popular, and composers found affinity with the divine musical gifts displayed by Orpheus.

Monteverdi took these ideas and created something new: The debut of L’Orfeo defied all previous musical convention. He placed words and emotions right at the forefront, subduing the traditional Renaissance polyphony (two or more lines of simultaneous independent melody) to emphasise one prominent melody line. He exploited dynamics and unprepared dissonance in order to convey human emotion, responding sensitively to the text. He was the first to create opera out of ‘real’ characters – living, breathing, emotional beings.

L’Orfeo was premiered at the Ducal Palace in Mantua – indications are of a small space, a narrow stage and an audience of only men. All of the performers were male, with castrati playing the female roles. The performance was successful enough that a repeat was demanded for all the ladies of the city to attend!

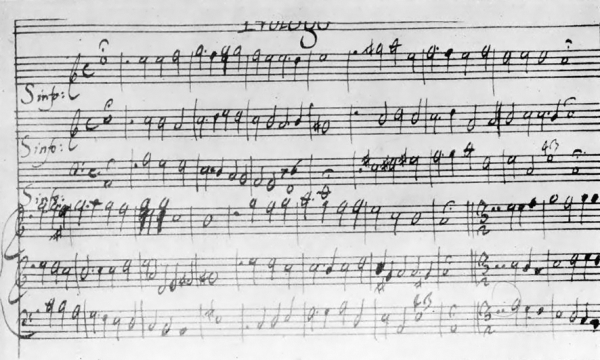

"Part of the uniqueness of the score lies in Monteverdi’s fragmentary markings and instructions. As was common for that period, Monteverdi encouraged instrumental ornamentation and embellishment, presenting his score as what today might be considered skeletal. This gives every performance of L’Orfeo its own distinct sound and identity." Tom Ford – Limelight Magazine

Image: Fragment of score for Poppea

The score also points to a composer in full command of his craft. It may be sparse, but it is not simple. Instrumentation was cleverly designed to characterise, and in some places, Monteverdi instructs what is to be played, not how: “Sung to the sound of five violins, three chitarrone, two harpsichords, a double harp, a double-bass viol and a sopranino recorder,” with only the vocal line and bass notated. This produces exciting challenges for modern performers.

Monteverdi’s second opera, L’Arianna, was completed a year after the tragic death of his wife. Sadly, like large swathes of Monteverdi’s work, this opera has been lost, save for Arianna’s Lament, which was so popular it was published separately several times.

In 1612, Monteverdi took a position as musical direct at the Basilica of St. Mark in Venice. During his latter years, when he was ordained as a Catholic priest, he composed much sacred music and music for civic occasions. Despite being ill much of the time, he also wrote two more operas, including L’incoronazione di Poppea, considered by many to be his finest work. Poppea contains romance, tragedy, and comedy – a new development in opera. The opera foreshadows those of Mozart, its complexity describing the triumph of evil over good through beautiful music.

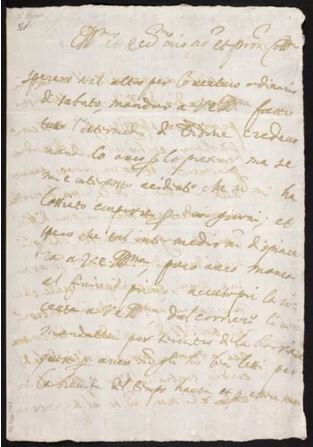

Monteverdi died at the age of 76 in Venice in 1643. His legacy of works fall into three categories: Madrigals, opera and sacred music. Over 50 of his letters survive, giving a wonderful view of Italy and of the 17th century.

Experience the Music of Monteverdi:

Share this post: