Kubrick and the Timelessness of Classical Music

Posted on 19th November 2018 at 14:00

2018 is the 50th anniversary of Stanley Kubrick’s groundbreaking science fiction film, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

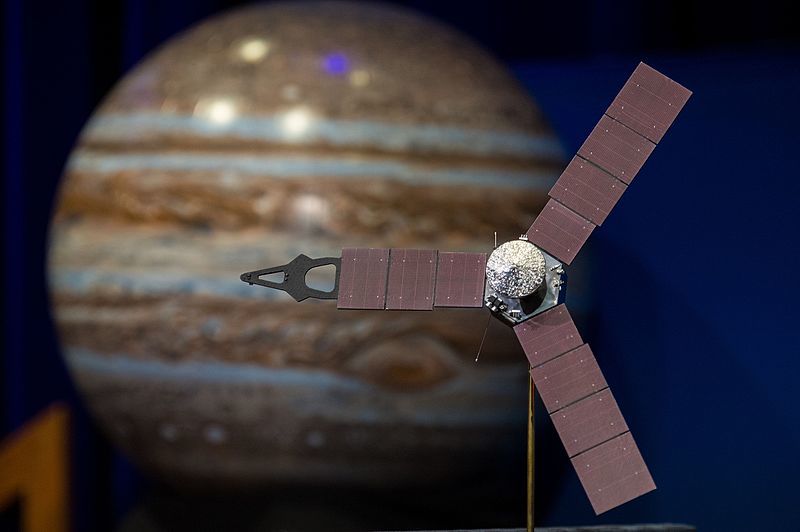

The narrative follows a voyage to Jupiter with a sentient computer called HAL. It explores themes of human evolution, technology, existentialism, artificial intelligence and the possibility of extraterrestrial life. The film features scientifically accurate depictions of spaceflight, ambitious imagery and groundbreaking special effects.

However, the aspect that arguably makes the film so memorable is the use of sound. Dialogue is sparse – there are only 40 minutes of it in a two and a half hour movie – and rather than the constant underscoring to which film audiences have become accustomed, almost no music is used in scenes with dialogue.

When there is music, the choice and use of music is significant. Whilst two composers, first Frank Cordell, then leading Hollywood professional Alex North were engaged to score the film, Cordell never got off the starting blocks, and Kubrick abandoned North’s score, deciding instead to use a selection of pieces of classical music – pieces that have now become synonymous with the film – marrying music from an age with which we might feel detached with an exploration of an age we have not yet lived.

In 1968 the use of classical music in films was not new (for example, David Lean used Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto to great effect in his film Brief Encounter in 1945) it had been standard practice since the dawn of the ‘talkies’ to score music directly for each film. In fact, a major part of the appeal for movie audiences was the chance to hear new, original music.

And film music had been as original as it comes from the start. For the 1951 film, The Day the Earth Stood Still, Bernard Herrmann pioneered an early form of multi-track recording, laying down the sound of two Hammond organs, a vibraphone, an electrically-amplified violin and a pair of Theremins. ‘

Seven years later, in 1958, Louis and Bebe Barron generated the world’s first all-electronic film score for Forbidden Planet. The score was so modernist that the studio billed them as creators of “electronic tonalities” rather than as musicians.

Despite his very different approach, Kubrick’s use of music was breathtakingly innovative, both in the illustrative power of music to support visual effects and in the way he managed to create such originality with pre-existing music.

Take the “stargate” sequence near the end of the film. It’s nothing more than a mosaic of brilliant colours rushing past and would have been completely ineffective without the music of György Ligeti, yet the scene was not conceived around the music any more than the music was written for the scene.

In this scene, the vast loneliness of space is wonderfully expressed in Khachaturian’s Adagio from the Gayane Ballet Suite.

Ligeti was understandably shocked on attending the Vienna premiere of the film to discover that four of his compositions had been used without permission. He was later to receive a modest payment from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios (MGM) and substantial royalties. However, by acknowledging Ligeti’s work in the final credits, Kubrick made the composer world famous and the two became friends over subsequent collaborations. Alex North was equally shocked to discover that his score had been totally dropped.

Although MGM Studios were not advocates of the ‘unoriginal’ soundtrack, they were perhaps instrumental in its existence. In March 1966, the studio had become concerned about the progress of the film. Kubrick put together a show reel of footage to an ad hoc soundtrack of classical recordings. The studio bosses were delighted with the results, and Kubrick abandoned North’s score in favour of his ‘guide pieces’.

Kubrick explained his reasoning in an interview with Michel Ciment:

"However good our best film composers may be, they are not a Beethoven, a Mozart or a Brahms. Why use music which is less good when there is such a multitude of great orchestral music available from the past and from our own time? When you are editing a film, it’s very helpful to be able to try out different pieces of music to see how they work with the scene…Well, with a little more care and thought, these temporary tracks can become the final score."

The most easily recognised piece and the one perhaps most associated with 2001 is the opening theme from the Richard Strauss tone poem, Also sprach Zarathustra(Usually translated as “Thus Spake Zarathustra” or “Thus Spoke Zarathustra”.

The theme is used both at the start and the conclusion of the film.

While the end music credits do not list a conductor and orchestra for Also Sprach Zarathustra, Kubrick wanted the Herbert von Karajan/Vienna Philharmonic version. Decca executives did not want their recording ‘cheapened’ by association with the movie, and so gave permission for its use on the condition that the conductor and orchestra were not named. When the movie was a massive success, the label tried to rectify its blunder by re-releasing the recording with an “As Heard in 2001” flag printed on the album cover…

The full track listing comprises only six pieces of music:

Also sprach Zarathustra by Richard Strauss

Requiem for Soprano, Mezzo-Soprano, 2 Mixed Choirs and Orchestra by György Ligeti

Lux Aeterna by György Ligeti

The Blue Danube by Johann Strauss II

Gayane Ballet Suite (Adagio) by Aram Khachaturian

Atmosphères by György Ligeti

The Blue Danube by Johann Strauss II

Also sprach Zarathustra by Richard Strauss

It’s notable that Kubrick’s spaceships waltzed to the Blue Danube by Johann Strauss II while NASA was girding its technological loins to put the first man on the moon.

Share this post: