The Extraordinary History of the Blues

Posted on 15th September 2015 at 16:00

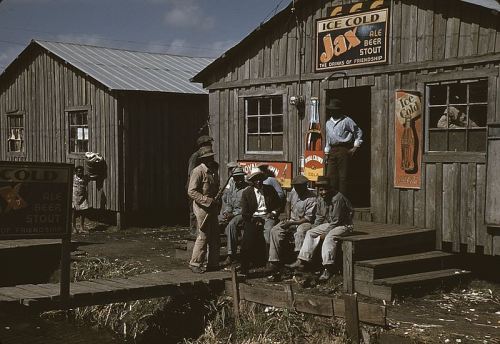

The Blues developed towards the end of the 19th Century. It was first heard among the African-American communities who farmed the plantations of the Delta, a flat plain between the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers, an area so characteristic of the Deep South that it has been called The Most Southern Place on Earth.

In the mid 1800s the area had been one of the richest for cotton growing in the United States, attracting many speculative farmers who were dependent for labour on black slaves.

Many people, both black and white, migrated to the Delta, working to clear land and sell timber, buying their own land from the proceeds. By the end of the 19th century, black farmers made up two thirds of the independent farmers in the Mississippi Delta, but in 1890, legislation was passed by the predominantly white government, effectively robbing them of their land.

Blues music grew from African music, influenced by the folk music of white European settlers. The term African music is very vague – there are at least as many kinds of music in Africa as there are in Europe, but the majority of slaves traded with the Americas came from West Africa.

Music in Africa developed very differently from European music too. Where the key element of European music was melody, embellished with counterpoint and set to rhythm, West African music focused on rhythmic counterpoint and timbre – in a sense both being extensions of the languages of the people.

Under the confines of slavery, this music changed and grew into new forms. By the mid 1700s, slavery required a justification, and conversion of slaves to Christianity became popular, even compulsory in some places. Hence, alongside the work songs, field hollers, shouts, chants, and simple narrative ballads, there also developed spirituals.

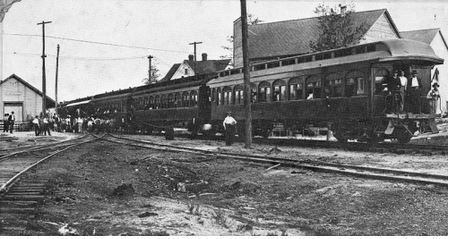

The social and economic reasons for the appearance of the Blues are unclear. Its origins are often dated to between 1870 and 1900, after the Emancipation Act of 1863. During this period, people were moving from slavery to sharecropping, small-scale agricultural production, and the expansion of railroads in the southern United States created new possibilities.

The Blues, which has its roots in the work songs and spirituals, shows a move from group performances to a more individual style, perhaps associated with the newly acquired freedom of an enslaved people.

Key aspects of the Blues form are call-and-response, the blues scale and traditional chord progressions. The most common format is the Twelve bar Blues. The blue notes, where pitch is altered, often flattened, are also an important part of the sound.

Where European music uses the diatonic scale, West African music uses a pentatonic scale that contains only the first, second, third, fifth, and sixth tones of the diatonic scale. As the music of Europe and Africa merged, two new scales developed, the deviant pentatonic scale of Spiritual music and the expanded diatonic scale of Blues music. All of black music in America, and ultimately western pop music, subsequently grew out of these two scales.

The lyrics of early traditional Blues verses consisted of a single phrase repeated four times. In the early 20th Century this developed into an AAB pattern made up of one line sung over the four first bars, its repetition over the next four, and then a second, longer line of lyrics over the last bars. Often the theme of the lyrics focused around troubles or problems, which is perhaps where the name Blues came from.

The Blues is now defined in terms of chord structures and lyrical form, but it was originally much more general. It was simply the music of the rural south. Black and white musicians shared the same song repertoire, though these were still the days of segregation so audiences were often all white. The notion of the Blues as a genre in its own right really arose during the migration of black communities from the countryside to urban areas during the 1920s. The recording industry was booming – the development of the coin-operated phonograph gave rise to juke-box arcades where people would go to dance and socialise after work – and many Blues songs were recorded to answer growing demand from black listeners.

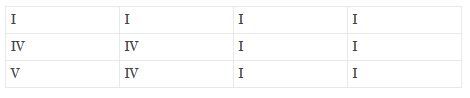

Twelve Bar Blues

The simplest form of Blues is the Twelve-bar Blues. It is usually a piece in 4/4 time and consists of 3 chords – chord I, IV and V.

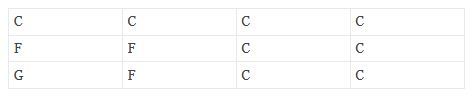

So in the key of C major, the chords would be:

A good way to explore the sound of the Blues is to practice singing the chord progression, starting with singing the root or tonic of each chord, then repeating adding the third, then adding the fifth.

Blues often use the blues scale which is based on the pentatonic scale but with an additional blues passing note. In the key of C the blues scales would be the fifth mode of the Eb pentatonic:

This sequence of notes can be played in any order over any of the chords in the C twelve-bar blues.

The styles, forms (12-bar-blues), melodies and scales of the Blues have had a huge influence on modern rock and roll, jazz and popular music. Prominent 20th century jazz, folk and rock performers, including Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Miles Davis and Bob Dylan were known for performing Blues, but it also influenced musicians including the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix, who between them had an explosive influence on the entire history of pop.

And not only is the blues scale used in popular songs, it’s even made its way into orchestral works such as George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue:

One of the most famous Blues songs is Saint Louis Blues by W. C. Hardy, published in 1914 (one of the very first songs to be printed), performed here by Louis Armstrong and Velma Middleton:

Early Rock and Roll songs such as Johnny B. Goode and Blue Suede Shoes clearly show the influence of the Blues, as does much R&B Music.

But perhaps the most prominent celebration of Blues came in 1980 in the film The Blues Brothers. The film brought together many of the biggest living influencers of the rhythm and blues genre, including James Brown, Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles and John Lee Hooker.

In 1998, the sequel, Blues Brothers 2000, featured artists such as Eric Clapton, B.B. King, Erykah Badu and Jimmie Vaughan, and in 2003, Martin Scorsese created a documentary film called The Blues for PBS for which he enlisted the help of directors Clint Eastwood and Wim Wenders. It’s available in its entirety on YouTube, but here’s the trailer to give you a taste:

Share this post: