Coleridge-Taylor Symphonic Variations on an African Air

Posted on 15th August 2023 at 12:49

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor is a composer whose popularity has grown and receded many times since he achieved fame with his trilogy of cantatas The Song of Hiawatha, which premiered in 1898. The Model Music Curriculum suggests listening to his Symphonic Variations on an African Air and possibly learning to sing the main melody, but this could also be a good introduction to starting to read a musical score.

British musicologist Herbert Antcliffe commented: "To those who really wish to know Coleridge-Taylor... no single work of his will reveal him more fully." Here, we explore the work and the man behind the music.

Life and Key Works

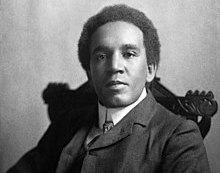

Coleridge-Taylor was born in Holborn in London in 1875, but grew up in Croydon, South London – a place where he is now celebrated. Coleridge-Taylor’s parents were Alice Hare Martin, an Englishwoman, and Daniel Peter Hughes Taylor, a Krio man from Sierra Leone.

Coleridge-Taylor was initially taught violin by his maternal grandfather, Benjamin Holmans, but when his talent became obvious he moved on to another teacher, and from the age of 15, he studied at the Royal College of Music in London. He changed from a focus on the violin to composition, studying with the composer Charles Villiers Stanford. On completing his degree, Coleridge-Taylor was appointed as a Professor at the Crystal Palace School of Music. He also began conducting the orchestra at the Croydon Conservatoire.

In 1898, Coleridge-Taylor’s Ballade in A minor for orchestra was performed at the Three Choirs Festival, after Edward Elgar had recommended him as "far and away the cleverest fellow going amongst the younger men".

In May 1898, Coleridge-Taylor’s most famous work The Song of Hiawatha, based on Longfellow’s 1855 poem, was completed and published. Even before its first performance, sales of the music were high. Unfortunately, due to financial pressures, Coleridge-Taylor sold the work to his publisher, Novello and so was not entitled to any royalties. The work was premiered on 11 November 1898 at the Royal College of Music, conducted by his former teacher, Stanford. There followed two further cantatas to complete the trilogy – The Death of Minnehaha was completed and premiered in 1899, and part three, Hiawatha's Departure, premiered on 22 March 1900.

In 1899, Coleridge-Taylor married Jessie Walmisley, whom he had met when they were both students at the Royal College of Music. The couple had two children, a son, named Hiawatha (1900–1980) and a daughter, Gwendolen Avril (1903–1998). They both had careers in music: Hiawatha adapted his father's works, Gwendolen became a conductor-composer, using the professional name of Avril Coleridge-Taylor.

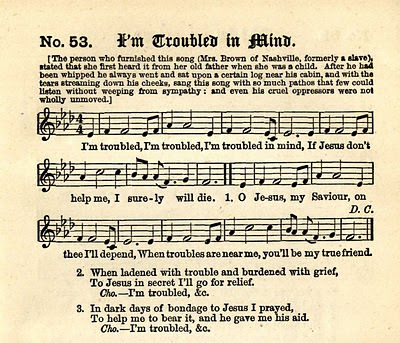

In 1905, Coleridge-Taylor published Twenty-four Negro Melodies Op 59. This was a collection of piano pieces based on melodies from Southeast Africa, West Africa, the Caribbean and the United States. Number 14 of this collection was an African-American spiritual, I’m Troubled in Mind which he later used as the theme in his Symphonic Variations on an African Air.

Coleridge-Taylor died in 1912, aged just 37, of pneumonia, a cause which is sometimes linked to his stressful financial situation. Following his death, King George V granted his widow, Jessie, an annual pension of £100, demonstrating the high regard in which the composer was held. Further support was garnered with a memorial concert which raised over £1,400 for the family.

Coleridge-Taylor’s financial situation fed a growing belief that musicians should be paid when their works were performed and not just on publication and distribution. As the Song of Hiawatha was one of the most popular works of the early 20th century, it was felt that it was unfair that the composer and his family received no additional payments. This case contributed to the formation of the Performing Rights Society (PRS) in 1914, which still ensures composers and songwriters receive payment for public performances of their work.

Symphonic Variations on an African Air

This work was composed between October 1905 and May 1906, with a premiere by the Philharmonic Society, conducted by the composer on 14 June 1906. The work uses a full orchestra of piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 French horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, harp, violins (divided into first and second violin sections), violas, cellos and double basses, and is the largest orchestra Coleridge-Taylor wrote for.

The piece is in variation form and is based on the African-American song I’m Troubled in Mind. This piece was included as number 53 in the songbook of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, a renowned acapella ensemble of Fisk University students.

The academic Catherine Carr, in her overview of Coleridge-Taylor’s life and work, suggests that the piece demonstrates that the composer had taken on board the views of his teacher, Stanford, on selecting a melody for use in variations:

“firstly, that it should contain sufficient material to vary; secondly, that it should have at least one striking feature; thirdly, that it should be simple.”

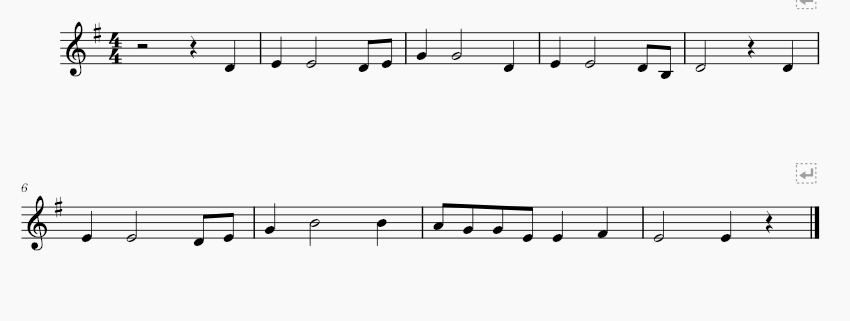

The main theme of the work is in two parts. The first is largely based on the pentatonic scale associated with folk music. Note that Coleridge-Taylor arranged the song in a different key to the original shown above.

However, if the theme is simple, the variations themselves are not simple – the variations mostly use a ‘“free’” technique similar to Elgar’s Enigma Variations – and so use a wide range of styles and characters. (For information about traditional Variation Form, click here.) The variations were not numbered by the composer and there is some debate about how many variations there actually are! Music Theory Professor John Snyder comments that this “speaks volumes about the ingenuity the composer exercised in shaping the work …”.

Snyder suggests that three topics dominate the overall scheme: sigh, dance and march. He uses these to suggests the following structure:

Theme

Variation 1 – Dance (+ March)

Variation 2 – Scherzo

Variation 3 – March / Sigh

Variation 2a – Scherzo

Variation 4 – Lyrical / Sigh

Variation 5 – Dance & March

Variation 6 – March (jaunty) & singing allegro

Variation 7 – Folk/pastoral + chorale + ombra

Variation 8 – Plaint / Sigh

Variation 7a – Folk/pastoral + chorale + ombra

Variation 9 – Dance (rustic) + march / military figures

Variation 10 – Sigh, arioso + military figures

Variation 11 – eEnergico (sigh transformed + military figures)

Variation 12 – March (risoluto)

Coda

The variations move between four and three crotchet beats in a bar (4/4 and 3/4).

Each of the variations are connected by transitions, which either help to move to the next key change (modulation) or to introduce elements of the forthcoming variation. This, again, means the piece is not a traditional theme and variations structure, demonstrating the influence of late 19th century composers.

Another area where the work deviates from traditional theme and variations is the wide range of keys the piece uses. Traditionally, this structure uses would use the same key throughout or closely related keys, such as the relative major / minor keys. (For more information on relative keys, click here).

Activities

A good starting point for this piece is to practise ‘active listening’ – for example, which instruments can you hear playing?

Listening to the music while following the score can be a great way to get to know pieces better.

The score for Symphonic Variations on an African Air is available for free download from ISMLP.

This version of the score is hand written so the notes are a little difficult to read, but you can see which instruments are playing.

For those not experienced in reading a full orchestral score, just focus on the first two pages of music (pages 7 and 8 in the score).

The music is written on the stave – the 5 lines. Each row of the stave (set of 5 lines) is allocated to one or two individual instruments (for the woodwind, brass and percussion) or to one section in the case of the strings.

The instruments are listed at the beginning of the first page in a traditional score order of:

• piccolo,

• 2 flutes,

• 2 oboes,

• 2 clarinets,

• 2 bassoons,

• 1st and 2nd French horns,

• 3rd and 4th French horns,

• 2 trumpets,

• 1st and 2nd trombone,

• 3rd trombone,

• tuba,

• timpani,

• percussion,

• harp (has 2 staves or sets of 5 lines as harp music is written in the same way as piano music),

• 1st violins,

• 2nd violins,

• violas,

• cellos,

• double basses

The piece starts with the Timpani playing repeated notes.

At the end of the second bar, the three trombone players begin the theme. Even though on the score it looks as though the trombones should be playing different notes, they are playing in unison (the same pitches). This is because the two staves have different clefs at the beginning of the line. The 3rd trombone has a bass clef, which you might be familiar with, but the 1st and 2nd trombone stave has a tenor clef, which is mainly used when writing for trombonists (but also sometimes cellists and bassoonists).

In the third bar, the string section (1st violins, 2nd violins, violas, cellos and double basses) join in, playing the accompaniment.

At the end of bar 10, the four horns join the trombones in playing the melody.

In bar 11, the flutes join in with the strings playing the accompaniment.

For Primary age children, they could mime to the instruments – trombones are particularly fun to mime to with their slide which changes the notes.

Further Reading

Carr, Catherine - The music of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912): a critical and analytical study -

Edmonds, Amy - Fisk Jubilee Singers - https://bsumc.blogspot.com/2011/02/fisk-jubilee-singers-america-robinson.html

Snyder, John L. - "Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s Symphonic Variations on an African Air, op. 63: Form, Techniques, Topics." - https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/inditheorevi.33.1-2.01

Share this post: