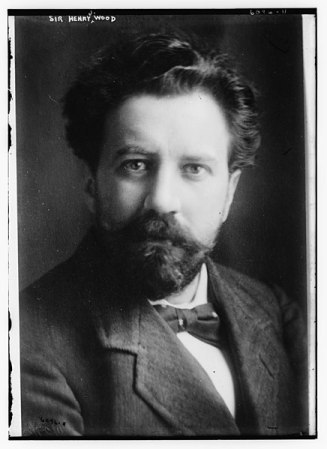

Movers and Shakers: Sir Charles Hallé and Sir Henry Wood

Posted on 13th March 2019 at 14:00

March 2019 is the 150th ‘birthday’ of Henry Wood, and April 2019 marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Hallé. Both men left a lasting musical legacy integral to the orchestral world in the UK. But where did they come from and what inspired their achievements? In this ‘double bill’ we celebrate the lives of two great musicians…

Sir Henry Wood, described in an interview in the Guardian from October 1938 as the ‘busiest and most versatile of Britain’s musicians,’ began his career conducting at a church choral society in 1888 where he earned ‘the enormous sum’ of two guineas.

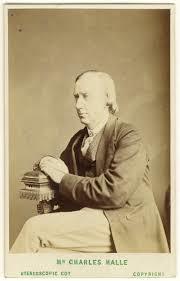

Pianist and conductor Charles Hallé was born Karl Hallé on April 11th 1819 in Hagen, Westphalia. His father, a choirmaster and organist, first introduced him to music, and he quickly excelled. He was a child prodigy, first performing a sonatina in public at the age of 4, and in 1828 he played in a concert where he attracted the attention of the virtuoso violinist (and inventor of the violin chin rest) Louis Spohr.

Sir Henry Wood, described in an interview in the Guardian from October 1938 as the ‘busiest and most versatile of Britain’s musicians,’ began his career conducting at a church choral society in 1888 where he earned ‘the enormous sum’ of two guineas.

Born within a stone’s throw of Oxford Street, Wood’s interest in music was encouraged by an intensely musical engineer father. Trained in the UK (he studied composition and voice at the Royal Academy of Music from 1886) he travelled widely to see and learn from great international musicians.

Often credited with founding the Proms, Henry Wood was instrumental in bringing the summer music series to London. He did so in partnership with the entrepreneur, Robert Newman who became manager and lessee of the newly opened Queen’s Hall in 1894, and Harley Street throat specialist, Dr. George Cathcart, who funded the first season. The vision was a series of classical concerts that anyone could attend, regardless of income. In 1895, Promming tickets cost one shilling, the equivalent of around 60p today.

It was Newman who devised the idea of Promenade concerts on the French model and who took on Wood as the sole conductor. However, while Newman and Cathcart’s input was essential, it was short lived. Newman went bust in 1902, and the main backer withdrew in 1926 leaving the Proms without support until the BBC took over in 1927, yet Henry Wood continued.

The first ever ‘First Night of the Proms’ was on August 10th 1895. 2,500 people gathered for the concert, which opened with the National Anthem. The programme featured popular works by Saint-Saëns, Haydn and Liszt, as well as London premieres of works by Chopin and Bizet. By the time of the 1938 interview, Wood was in his 44th season at Queen’s Hall, and had conducted nearly 3,000 Promenade Concerts, nearly 1,000 Sunday concerts and 600 symphony concerts.

The 1939 Proms season was abandoned after only 3 weeks following the declaration of war: The season, which had opened during the Battle of Britain, was forced to close early due to the Blitz. The concert on September 7th 1939 was the last Prom concert to take place at the Queen’s Hall, as the building was destroyed when a bomb hit the roof on 10th May 1941. In its 50th season, now at the Royal Albert Hall (RAH), the Proms again finished early because of the war, but concerts scheduled for broadcasting continued from the BBC’s Bedford wartime studios.

Wood was a charismatic presence on stage, embracing a new German style of conducting where the conductor’s role was much more expressive, not confined to keeping time. And he had a voracious appetite for music of all kinds. He and Newman had been determined to introduce a broad range of music to a wider audience, working to democratise the genre. The concert atmosphere was informal, with eating and drinking allowed during the performance, and the music had to be popular.

As the seasons progressed, Wood developed an enterprising, challenging and entertaining selection of music, always programming new works. He conducted an astonishing list of premieres during his career: 716 works by 356 composers, including Debussy’s L’Apres-midi d’un Faun. In fact, he was responsible for introducing many of the leading composers of the day to the Proms audiences, including Richard Strauss, Debussy, Rachmaninov, Ravel and Vaughan Williams. He was also passionate about promoting young and talented performers, and worked to raise the standard of orchestral playing.

[Image by: Ed g2s/wikicommons images]

Wood passed away on 19 August 1944 aged 75. He had conducted at the Proms for nearly 50 years. After his death, the concerts were renamed the “Henry Wood Promenade Concerts”, and the Proms continues as the longest running series of orchestral concerts in the world. Henry Wood is remembered every year, by the placing of a bronze bust (borrowed from the Royal Academy of Music) at the back of the RAH stage. His legacy is celebrated at the Last Night concert when a member of the audience drapes a wreath around the neck of the bust and the conductor leads ‘three cheers’ for Henry Wood.

Pianist and conductor Charles Hallé was born Karl Hallé on April 11th 1819 in Hagen, Westphalia. His father, a choirmaster and organist, first introduced him to music, and he quickly excelled. He was a child prodigy, first performing a sonatina in public at the age of 4, and in 1828 he played in a concert where he attracted the attention of the virtuoso violinist (and inventor of the violin chin rest) Louis Spohr.

Aged 16, he studied at Darmstadt with the organist and composer Rinck, and at 17 he went to Paris, where he stayed for 12 years. Whilst in Paris, he knew everybody worth knowing, counting musical greats including Cherubini, Chopin, Liszt and Wagner among his friends.

His time in the French capital ended with the February Revolution of 1848. Hallé had begun a series of chamber concerts in a small room at the Conservatoire, but the third series was cut short by the revolution and finding musical life in Paris had suffered after the revolution, he left for England.

His first appearance in his new home country was as soloist in an orchestral concert at Covent Garden, May 12th, 1848, where he performed Beethoven’s Concerto in E flat. In fact, the familiarity of the Beethoven piano sonatas in England is largely due to Hallé, who was the first pianist to play the complete series here.

He was also the inventor of a mechanical page-turning device for pianists. The pages were set into the mechanism, which was operated by means of a foot pedal. According to Harold C Schonberg’s 1963 book, The Great Pianists: “People would go to his concerts just to see the spectacle of leaf after leaf turning over, ghostlike, without the intervention of human hands.”

But Hallé didn’t much like London, and in 1853 he accepted an offer to run Manchester’s Gentleman’s Concerts, which had its own orchestra. This orchestra was apparently so bad that Hallé considered returning to Paris, but he was industrious and meticulous. Being the type of person who would not open a letter until he had answered all previous correspondence, he taught himself English every morning on the way to work, and he stuck with the orchestra.

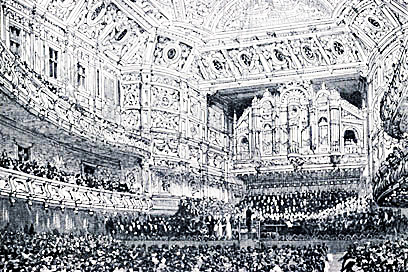

In May 1857, Hallé was asked to put together a small orchestra to play for Prince Albert at the opening ceremony of the Art Treasures of Great Britain. This was the biggest single exhibition Manchester had ever hosted. Hallé accepted the challenge and was so happy with the results that he kept the group together until October. This was the beginning of the Hallé Orchestra, now one of the oldest professional orchestras in England.

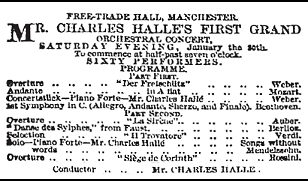

Hallé went on to start his own concert series, raising the orchestra to a standard far higher than normal for English music at that time. He decided to keep working with the musicians on a more formal basis, and on January 30th, 1858, the Hallé gave its first concert.

He conducted almost every concert and performed as piano soloist at many, until his death in 1895. He excited the public about music, raising standards and expectations, and introducing new concepts and works including premieres of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique and The Damnation of Faust.

A passage in the 1890 publication Manchester Faces and Places describes the change in attitude to music during Hallé’s time in Manchester:

"… he declares his conviction that the progress of music in England has been greater during that time than in any other country."

This remark is illustrated by several anecdotes including this:

"At that period [Hallé] discovered that if he asked a gentleman in society, ‘Do you play an instrument?’ this appeared to be considered an insult. Did not Lord Chesterfield indeed warn his son not ‘to fiddle,’ on pain of forfeiting his claim to rank as a gentleman? But since then how great is the change! A love of music is now becoming the common passion uniting all classes. A few years ago Sir Charles Hallé was waiting for the train at Derby, when a railway porter who recognised him said, ‘Can you tell me, Mr. Halle, when the ‘Elijah’ will be next performed in Manchester, because I can have leave to take my missus there?’ Only the other day a music-seller in Sheffield, who is in a position to know, assured Sir Charles that there are in that town alone between five hundred and six hundred artisans who play the violin."

Hallé’s death on October 25th, 1895, shook Manchester and the wider musical world, and his funeral procession brought the city to a standstill. Three of his closest friends, Henry Simon, Gustav Behrens and James Forsyth, immediately set about securing the future of the Orchestra, guaranteeing the 1895-96 season against loss. This commitment was renewed for a further three years whilst the Hallé Concerts Society was formed. Under the guidance of such distinguished conductors as Hans Richter, Sir Hamilton Harty and Sir John Barbirolli the Orchestra continued to thrive and develop.

In an interview for the Telegraph, Mark Elder, current music director of the Hallé since 2000 (seen in the image above with the orchestra in 2011), explains the driving force in the success of the orchestra both then and now:

"One way in which Hallé was ahead of his time was his understanding that education is absolutely key to an orchestra’s success. When you understand something, you enjoy it. That’s why he was so keen to bring the latest music to England, and why he was the first person to play a complete cycle of Beethoven piano sonatas.

He also understood that to reach a public you have to make the effort to go out to them. Part of the secret, I feel, is to link the orchestra to its community in a way that goes beyond concert-going."

Both Hallé and Wood were passionate, not only about their own musical careers, but about sharing their love and excitement for music with the wider community. The legacy of these two historic artists centres around what is now a formal body of classical music but one which, in the case of both the Hallé and the Proms, still works to engage the wider community in as many ways as possible, staying true to its original intent. It is almost impossible to quantify the value of those musicians who work so hard to share their gifts, except in the enjoyment of the opportunities and organisations they leave behind, whatever the challenges they faced. In a time when the future of music in education is unclear, it is encouraging to understand how much difference one person with talent and vision can make.

Share this post: